In January 2020, the top law enforcement agency in the state of Oregon launched a “Bias Response Hotline” for residents to report “offensive ‘jokes.’”

Staffed by “trauma-informed operators” and overseen by the Oregon Department of Justice, the hotline, which receives thousands of calls a year, doesn’t just solicit reports of hate crimes and hiring discrimination. It also asks for reports of “bias incidents”—cases of “non-criminal” expression that are motivated, “in part,” by prejudice or hate.

Oregonians are encouraged to report their fellow citizens for things like “creating racist images,” “mocking someone with a disability,” and “sharing offensive ‘jokes’ about someone’s identity.” One webpage affiliated with the hotline, which is available in 240 languages, even lists “imitating someone’s cultural norm” as something “we want to hear” about.

It is not entirely clear what the state does with these reports. While the hotline cannot “sanction a bias perpetrator,” according to its website, it does share “de-identified data” with the Oregon Criminal Justice Commission, a body that develops “public safety” plans for the state, and connects “survivors” with “resources” like counseling and rent relief.

To find out more, the Washington Free Beacon called the hotline and reported a fictitious incident. Here’s how that conversation went.

Describing himself as a Muslim concerned about the “genocide” in Gaza, this reporter said he felt “targeted” by an Israeli flag on his neighbor’s front door, adding that his neighbor had displayed the flag after the two had an awkward exchange about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Within 20 minutes, a hotline operator had logged the display in a “state database,” referred to it as a “warning sign,” and suggested installing security cameras in case the situation “escalates.” He also informed this reporter that, “as a victim of a bias incident,” he could apply for taxpayer-funded therapy through the state’s Crime Victims Compensation Program, which covers counseling costs for bias incidents as well as crimes.

The Free Beacon had provided no evidence of danger and was reporting a religious and political symbol. All that mattered, according to the operator, was how the symbol had been perceived.

“Even if it is not very explicit, we go with whatever the victim is experiencing,” the operator said. “And if your sense is that this is based on discrimination against your faith or your country of origin … that’s how I would document it.”

A hotline that lets people report their neighbors for “offensive” flags—based solely on the feelings of those offended—sounds more at home on a college campus than in a state government bound by the First Amendment. But Oregon isn’t an outlier. It is one of a dozen Democratic jurisdictions, including eight states, that have created bias reporting systems for residents to report protected speech.

Connecticut’s system lets users flag “hate speech” they “heard about but did not see.” Vermont tells residents to report “biased but protected speech” directly to the police. Philadelphia has an online form that asks for the “exact address” of the “hate incident,” as well as the “name” and gender identity of the offender—information the city uses to contact those accused of bias and request that they attend sensitivity training.

“If it is not a crime, we sometimes contact the offending party and try to do training so that it doesn’t happen again,” Saterria Kersey, a spokeswoman for the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations, told the Washington Free Beacon. The offender is free to decline, she said.

The systems, which include hotlines and online portals, resemble the bias response teams commonplace on college campuses, which allow students to report each other, anonymously and without verification, for ideological faux pas. What sets the state-run systems apart are their ties to law enforcement.

Some of the hotlines share data with policymakers and the police on the grounds that “biased” speech, while not actionable in itself, can lead to hate crimes.

“People who engage in bias incidents may eventually escalate into criminal behavior,” reads a report from the Maryland attorney general’s office, which maintains its own bias reporting system. By collecting data on those incidents, states say they can predict where hate crimes will occur and develop strategies for combating them.

Such number-crunching need not violate anyone’s privacy, officials in Maryland and Connecticut told the Free Beacon. The systems, they said, are not used to spy on individuals but to track statewide trends.

But where bureaucrats see a form of data collection, others see a regime of social control. Civil liberties advocates argue that the mere possibility of ending up in a government database will encourage citizens to self-censor and that bias reporting systems push the bounds of what is permitted by the First Amendment. They also worry that even if the systems stay within those bounds, they are fomenting a culture antithetical to self-government—one in which snitching is normalized as a state-sanctioned practice.

“We associate snitching with some of the most oppressive regimes throughout history,” said Nadine Strossen, a past president of the American Civil Liberties Union. “The Stasi comes to mind.”

At a time when “wokeness” is ostensibly on the back foot—major companies have axed their DEI programs, top universities have stopped requiring diversity statements, and Donald Trump has been reelected president—the systems suggest that reports of its death have been greatly exaggerated. They illustrate how technologies pioneered on campus can be repurposed by state governments. And they raise the possibility that those technologies will outlive the cultural moment that produced them, blanketing the United States, or at least the blue areas of it, in a permanent layer of surveillance.

“Exporting campus bias reporting systems to wider society is a disastrous idea,” said Aaron Terr, the director of public advocacy at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE). “When a state policy explicitly calls out ‘offensive jokes,’ it’s past time to worry.”

“If you see something, say something”

The First Amendement protects slurs, swastikas, and even calls for genocide. It does not, however, bar governments from providing “support” to people “harmed by protected speech,” in the words of a 2022 report from the Vermont attorney general’s office. And amid the cultural aftershocks of George Floyd’s death, many states seized on that loophole to justify a new form of surveillance.

California, Illinois, and New York all set up systems to report not just hate crimes but “bias incidents,” defined as any expression of bias against a protected class that does not rise to the level of a crime. Washington state will launch its own system this year. Local-level systems exist in Westchester County, N.Y., Montgomery County, Md., Eden Prairie, Minn., and Missoula, Mont.

By the end of 2025, nearly 100 million Americans will live in a state where they can be reported for protected speech.

Some states frame their systems as victim support services that offer referrals to counseling and legal aid. Others, though, imply that the systems function more like a form of predictive policing—the use of data and algorithms to forecast criminal activity—in which bias incidents serve as data points that are used to predict hate crimes.

In Vermont, police use reports of “protected ‘hate speech’” to “identify community conflicts that may lead to unlawful activity,” according to a statewide police protocol adopted in 2019. While enforcement action “may not be possible” in those cases, the protocol states, “complaints of such incidents should be documented and taken seriously.”

Other states claim not to monitor individuals but say that the data from their systems help identify criminal hotspots. Connecticut’s online portal says the state “will use this information to determine when and where hate incidents occur, improve resource allocation, and develop community anti-bias programs,” adding that “information may be shared with law enforcement.” California’s portal says reports will be used to “identify areas in need of more resources related to acts of hate.” Maryland’s portal says that reports will inform the work of the state’s Commission on Hate Crime Response and Prevention, a task force in the Maryland attorney general’s office, by “identifying trends in hate crimes and hate bias incidents.”

It is not entirely clear how those trends are identified, but most of the systems ask for the location of the incident, the protected class that was “targeted,” and a description of what happened. Some also let users upload photos and videos of the incident. And a few, including Philadelphia’s and Westchester County’s, ask specifically for offenders’ names.

The rest allow names to be reported by phone or through an open text field, though officials in Maryland and Connecticut told the Free Beacon that their states do not keep a record of that information. California’s civil rights department said that its portal is not “intended to collect or store the names of alleged perpetrators,” but declined to specify what happens when they are reported through an open text field. Other states, including Oregon and New York, said that identifying information is retained but not subject to public disclosure.

Some of the systems claim to be separate from law enforcement but encourage people to contact the police over non-criminal offenses. In September, for example, the Free Beacon created an X account, “racisttroll_12,” and had it refer to another Free Beacon-created account—characterized as a “non-binary poc”—as a “man.” When this reporter uploaded a screenshot of the interaction to Maryland’s portal, describing it as an act of “misgendering,” a member of the state’s hate crimes commission, Jennifer Frederick, acknowledged that no crime had been committed but suggested calling the police anyway.

“You can reach out to your local police to report a hate bias incident,” Frederick wrote in an email. By keeping track of those incidents, which “fall below the level of a crime,” Maryland can “monitor hate activity” and “take actions … to prevent further hate in the future.” Frederick added that police will not keep a record of who said what “if they determine this does not rise to the level of a crime.”

The Maryland attorney general’s office said that police record incidents of hate speech so they can be included in the state’s annual hate crime reports. The Vermont attorney general’s office, which receives reports of hate speech from the state’s police, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

For Terr, FIRE’s director of public advocacy, the involvement of law enforcement raises serious questions about the systems’ constitutionality and their potential chilling effects.

“Some courts have ruled that campus bias response teams chill protected speech through implicit threats of investigation and punishment,” Terr told the Free Beacon. “The state-level reporting systems raise similar First Amendment issues, especially when law enforcement is involved.”

Other experts said the legality of a given system would depend on what information is retained, how it is used, and whether a reasonable person would be deterred from exercising their First Amendment rights.

Collecting de-identified data is “perfectly legal,” said Samantha Harris, a First Amendment attorney. “But it’s legally questionable if names end up in any kind of database.”

Strossen, the former ACLU president, said that the chilling effect would be especially pronounced if, as in Philadelphia, state or city officials contact people about their allegedly offensive speech.

“There’s a very strong argument that would be considered a violation of the First Amendment,” she said. “If I received a call like that, it would feel very targeted and intrusive.”

A few states imply that the potential to chill speech is a feature, not a bug, of their reporting systems. Illinois’s hotline says that “reporting hate” is valuable because it “sends a message” to “offenders” that “hate will not be tolerated.” And Connecticut’s Hate Crimes Advisory Council, which oversees the state’s reporting system, has said that it aims to prevent bias incidents—not just hate crimes—”before they occur,” likening its efforts to an anti-terrorism campaign.

“One of our goals is to make Connecticut a state where people who express and spread hateful ideas do not have a receptive audience or climate,” the council wrote in a 2022 report. “One of our principal recommendations is a vigorous public interest campaign—similar to the anti-terrorist ‘If You See Something, Say Something’ model—making it clear that Connecticut is ‘No Place For Hate.’”

The Illinois Commission on Discrimination and Hate Crimes did not respond to a request for comment. Ken Barone, a project manager at the University of Connecticut’s Institute of Municipal and Regional Policy, which summarizes reports of bias incidents for law enforcement, said the state’s portal was “still in testing” and deletes information “on a weekly basis.”

Most states are careful to distinguish hate speech from hate crimes and note that they can only punish the latter. But Strossen, who has spent her career advocating for a culture of free speech, said it is precisely that distinction that bias reporting systems threaten to undermine.

“Permitting people to report hate speech is already very troublesome, even if the records are destroyed,” she said. “It foments the notion that hate speech is equivalent to hate crime, that speech is equivalent to violence.”

That “pervasive misunderstanding,” she added, “is what led to the degradation of free speech on campus.”

“I want to center your perspective”

At universities, the knock against bias reporting systems has always been their subjectivity. Critics say these systems employ a vague definition of “bias” that can encompass practically anything that someone, somewhere, might find offensive, from edgy Halloween costumes to milquetoast political statements.

Campus bias response teams “are easily weaponized to censor unwanted views,” said Cherise Trump, the executive director of Speech First, a First Amendment watchdog. “Students tend to use these reporting mechanisms to report their peers with whom they have political disagreements.”

Now, as those systems metastasize from the seminar to the state, ordinary citizens are engaging in the same sort of snitch culture that has chilled campus debate. People in Oregon and Vermont have been reported for a wide range of political expression, according to reports from both states, including “efforts to defund city diversity initiatives,” protests of controversial books in schools, editorials that question the “extent of race discrimination,” and displays of pro-Trump flags.

Other regions do not publish examples of the reports they’ve received, but indicate that “bias incident” is a broad category, encompassing “hate material on one’s own property” in Maryland and the “threat of outing” in Missoula.

The range of reports reflects the subjective definition of bias used by the systems, which, as the Oregon hotline operator put it, “go with whatever the victim is experiencing.”

“I want to center your perspective,” the operator told the Free Beacon in response to this reporter’s complaint about the Israeli flag. “If you feel like there is an expression of animus against your religious beliefs, then that’s a bias incident.”

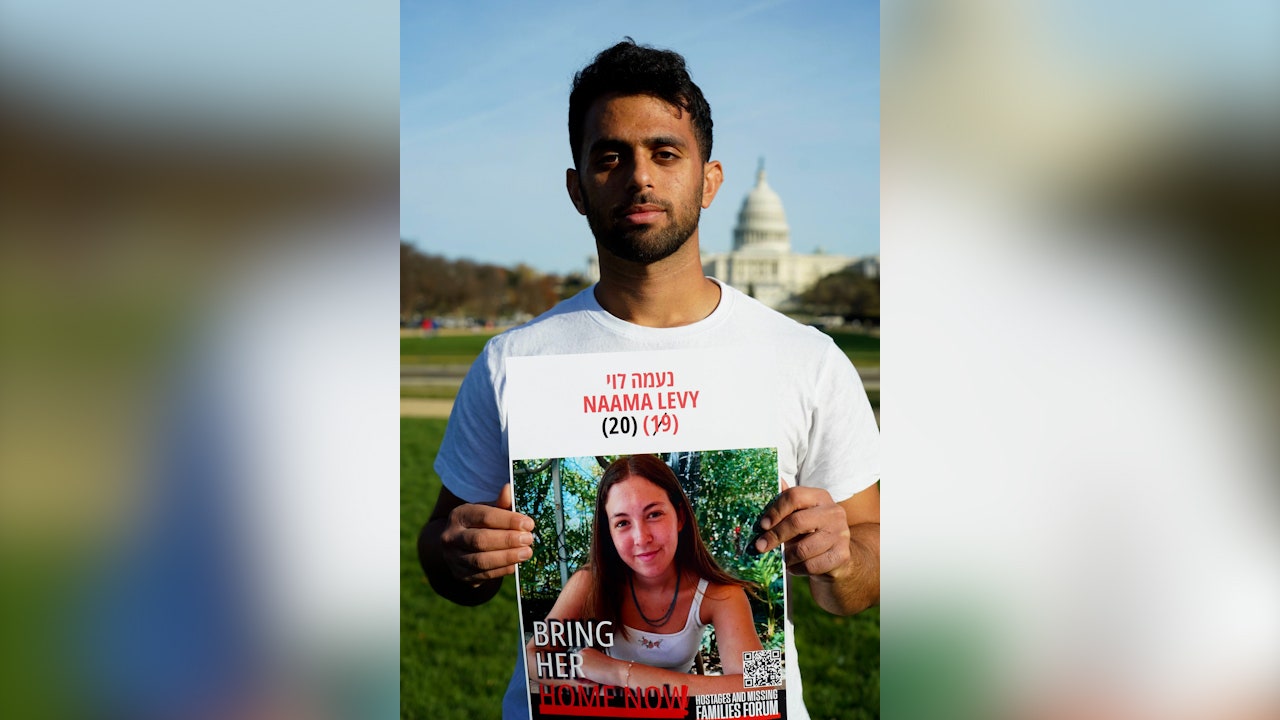

The hotline, which can also be reached via online chat, appears to apply that principle consistently. When the Free Beacon submitted a separate complaint about a “From the River to the Sea” sign, the hotline logged that as a bias incident, too.

![]()

Once again, an operator suggested it might be wise to install security cameras, adding that the state has a “small pot of money” to help victims pay for them.

![]()

Asked about therapy, the operator referred this reporter, who had identified himself as Jewish, to a nonprofit, Raíces de Bienestar, that runs mental health programs for the “Latino community.”

“They have therapists that speak English,” the operator explained. “It is a service for the Latino community but they do not turn anyone away.”

![]()

That two opposing views can both be logged as bias incidents—in the context of one of the most divisive issues in the world—”shows how open-ended definitions of bias can encompass even common forms of political expression,” Terr said.

It also raises the possibility that a system built to police one kind of speech will be used to police others, creating a panopticon in which all citizens, no matter their politics, are subject to surveillance.

“When you build structures for censoring and monitoring citizens’ speech, the structure can be used to monitor any viewpoint,” Harris told the Free Beacon. “Having anonymous tip lines for offensive speech is not a good thing, regardless of whose speech it is.”

Read the full article here