In Unremitting: The Marine “Bastard” Battalion and the Savage Battle that Marked the True Start of America’s War in Iraq, author Gregg Zoroya takes readers on an intense, often violent journey with a Marine battalion that fought in some of the toughest fighting in American history—the Battle of Ramadi, Iraq, in the summer of 2004. Incredibly detailed, Unremitting provides a day-to-day—and in many cases a minute-by-minute—narrative about the 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines (2/4) and the punishing warfare it faced over 184 days in the provincial capital of Ramadi. Over that deployment, the 1,000-man battalion suffered 238 Marines and sailors wounded and 34 dead, a whopping casualty rate of roughly 30 percent, the highest of any battalion in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Zoroya takes readers back to the spring and summer of 2004, a dark time for the United States as the situation in Iraq deteriorated drastically. The insurgency was growing in scope and intensity, with particularly harsh fighting in Fallujah and Ramadi—the 2/4 suffers casualty after casualty from IEDs and roadside bombings, ambushes, and intense firefights.

There are numerous harrowing episodes sprinkled throughout, like the story of two young Marines trapped in a carport in the middle of some godforsaken Ramadi neighborhood, cut off from their squad, and surrounded by enemy fighters. Or the young Marine all alone in an abandoned house, shot in both arms with enemy fighters advancing in an unrelenting and terrifying march toward him. Or the hidden sniper team of four Marines who was spotted by an Iraqi child and the teams’ gut-wrenching discussions on how to handle the situation.

Readers have to wonder: Would I have the self-control to survive that moment? The answer for these young Marines was an emphatic “Yes.” And that is one heartbreaking aspect of the story: just how young these Marines were, 18- and 19-year-olds making life-or-death decisions and being thrust into unimaginable situations.

Make no mistake: This book is not for the faint of heart, with gruesome moments, such as an IED attack that blew off a Marine’s jaw, his comrades searching for pieces of it in the dirt and placing them in MRE bags. Zoroya presents those horrific events with a reporter’s remove, simply conveying the facts for the readers in direct and unsparing prose. Writing of a beloved sergeant, Zoroya notes: “When one of his men was decapitated by a rocket-propelled grenade round, [the sergeant major] assumed the grim task of picking up the shards and slippery shreds left behind.”

The book is remarkably well-researched, featuring a mix of quotes from the Marines, soldiers, and sailors, documents, letters, and after-action reports, which Zoroya capably uses to place the reader in the Marines’ shoes throughout the highly kinetic action. Readers’ heart rates will inevitably spike in some difficult moments, like the dogged engagement in Ramadi’s East Cemetery at the very outset of the battle on April 6.

As with any deployment in a combat zone, the 2/4 suffered a series of setbacks, from catastrophic ambushes to guns jamming at critical moments, from deadly miscommunications to wrong turns in bad neighborhoods, from possible friendly fire to extreme heat that led to heat exhaustion in their heavy gear, and from impossibly difficult dilemmas for young squad leaders to double-crossing Iraqi officials.

There was also plain, old dumb luck. Amid a horrible ambush in which the enemy sent volley after volley of rocket-propelled grenades, two of the RPGs hit a 2/4 vehicle. One RPG that would have been a devastating direct hit turned out to be an inert, non-explosive training round, and the other struck a passenger door of a Humvee and simply slammed it shut without exploding.

And there are also moments of levity. The book opens with a humorous anecdote that occurred stateside right before the 2/4, which goes by the nickname “The Magnificent Bastards,” deployed in February 2004. A commanding officer invited the officers of the 2/4 and a peer battalion to a white-tablecloth Valentine’s Day party. The soiree quickly degenerated into a melee straight out of Animal House, with 2/4 Marines drinking from the table centerpiece vases (including the goldfish that swam inside), plates and dishes flying, and an overturned porta-potty with a 2/4 Marine inside. Magnificent Bastards, indeed.

Hands down, the funniest moment in Unremitting involves a lance corporal enjoying some private time in the only place the Bastards could be alone: the porta-potty. In a remarkable stroke of bad luck, insurgents launched a mortar attack in the middle of his “alone time.” The unfortunate lance corporal had to run out of the potty, holding his gun and wearing a gas mask, all with his pants down by his ankles. (Shrapnel from a mortar hit him as he stumbled toward the barracks, so he received a purple heart. It is unclear whether that is the first purple heart awarded to a Marine for injuries suffered while pleasuring himself.) “Those were the kinds of images the Marines loved to recollect,” Zoroya writes, “memories stacked up neatly at the intersection of hilarious and harrowing.”

Those moments, however, are few and far between. Unremitting is a war book, after all, and it presents a relentless drumbeat of tough fighting. By the third day of the April battles, it can feel repetitive. But that is probably the point: The Marines were locked in a hopeless cycle of fighting with an intractable, organized, and highly unorthodox enemy.

Perhaps the best passage in the entire book summarizes the experience of Unremitting and shows Zoroya at his best:

If it all sounded bat-shit crazy, that’s because it was. The Marines, after all, were living in a dangerous city among people who wanted them dead. They were preoccupied with not being maimed by a mortar round or obliterated by an IED or shot by a sniper or thrust into a kill-or-be-killed gunfight. They were adapting to this madness, even becoming seasoned at it. But there was still life in the margins where basic human needs and desires existed. A good night’s sleep. A decent meal. … Just plain missing wives or girlfriends or parents or children. Or sex. Trying to reconcile those longings with the reality and demands of Ramadi was preposterous, and it was folly to even try. All a sane person could do once in a while was laugh at it.

Unremitting: The Marine “Bastard” Battalion and the Savage Battle that Marked the True Start of America’s War in Iraq

by Gregg Zoroya

Grand Central Publishing, 432 pp., $32.50

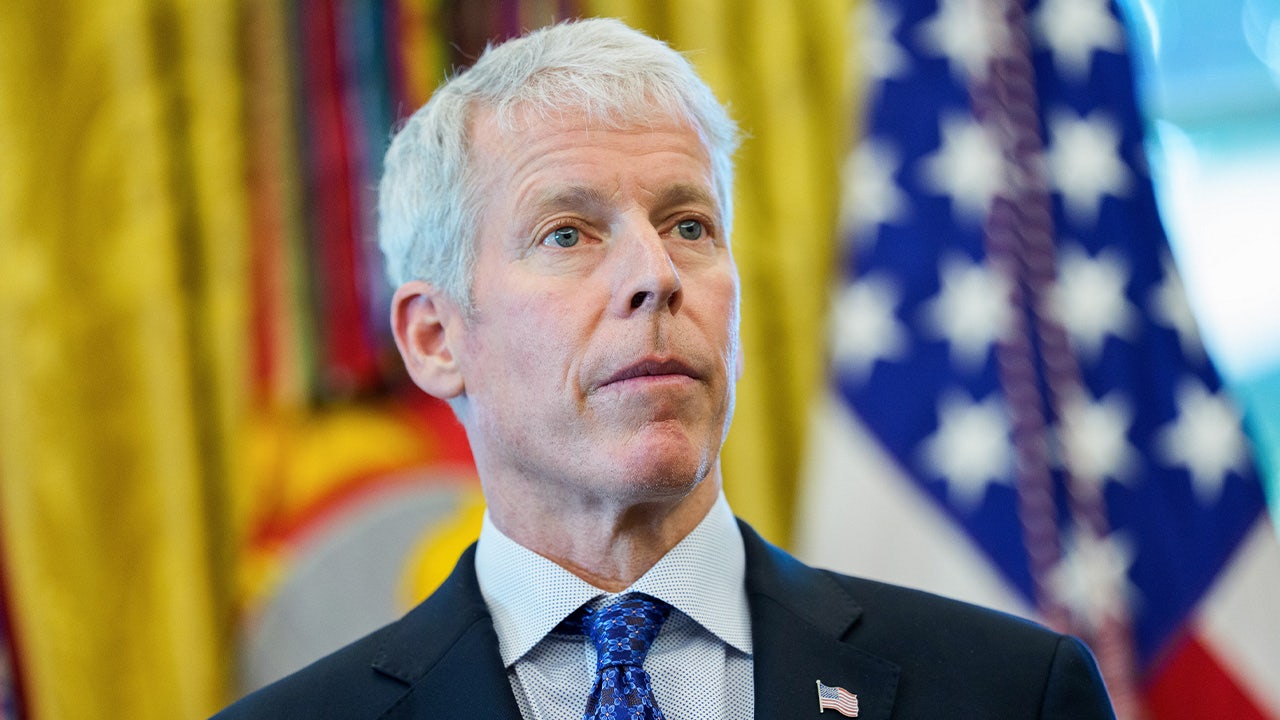

Mark Lee Greenblatt, a former inspector general of the U.S. Department of the Interior and chair of the Council of Inspectors General, is the author of Valor: Unsung Heroes from Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Home Front (Taylor Trade).

Read the full article here