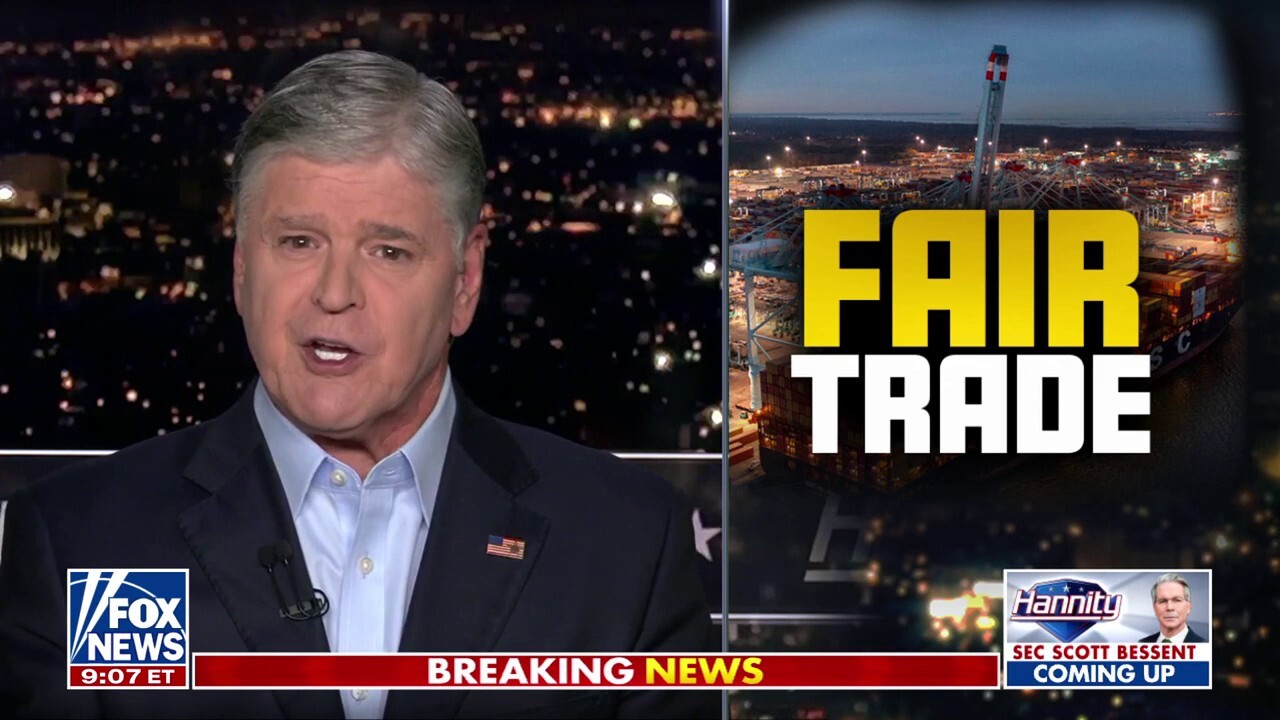

As peace remains elusive in Ukraine, it’s worth reflecting on a time when the region was similarly witness to carnage—but with the Russians fighting the British, French, Turks, and… Sardinians?

Gary Saul Morson returns to the Weekend Beacon with a review of Gregory Carleton’s Crimean Quagmire: Tolstoy, Russell and the Birth of Modern Warfare.

“In this riveting account of the war, Gregory Carleton, the foremost expert on the Russian understanding of war, argues for its importance. ‘Crimea changed the face of modern warfare forever,’ he claims in Crimean Quagmire. For one thing, it featured several technological firsts. The Russians’ old-fashioned musket was no match for the modern rifle wielded by the British and French. Standing at a distance that muskets could not reach, they were able to annihilate Russian regiments. Long-range artillery came into use, and here the Russians did not lag behind. By using the new steam-powered ironclad ships firing explosive shells, the Russians were able to destroy the Turkish Navy of wooden sailing ships. Landmines, or ‘man-traps,’ killed people long after a battle was over. The railroad, telegraph, and photography became part of warfare. On the plus side, anesthetic chloroform made operations bearable. A Russian doctor, Nikolai Pirogov, introduced triage surgery so treatment could be given first to those with a chance to survive. Taken together, Carleton observes, these innovations ‘represent the greatest revolution in warfare since the introduction of gunpowder.’ It was, in short, ‘the first ‘modern’ war.’

“And yet it was also the last war in which most military casualties took place off the battlefield. Soldiers were far more likely to die from disease, exposure, and hunger than in combat. That had always been the case, but it now shocked popular opinion because these deaths were almost entirely preventable. Lack of foresight, poor planning, incompetence, indifference, and above all bureaucratic morass resulted in the death of tens of thousands. Although the cause of scurvy was well known, British soldiers suffered from it because they were given a diet without fruits and vegetables. People at home learned of these failures because of what Carleton considers the most important innovation of the war: near real-time accounts of it. British soldiers, most of whom were now literate, wrote letters about their experiences and, especially important, journalists did on-the-spot reporting.

“The most influential British paper, The Times, dispatched William Howard Russell as what we now call an ’embedded’ reporter, and his stories, which continued until the war concluded, moved the British public as never before. Such frankness was of course impossible in the empire of the tsars, but tales written by a young junior officer, who was just beginning to be well known, were widely read, as they still are. The officer’s name was Count Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy, and the lessons he learned about how battle is really conducted were to shape the greatest novel of world literature, War and Peace, which described war realistically for the first time.”

Talk about a descent into the maelstrom, Micah Mattix reviews Edgar A. Poe: A Life by Richard Kopley.

![]()

“When Poe was sober, he was a model employee. He would sit at his desk and produce reams of criticism for whatever weekly he was working for at the time, as well as short stories and poems. George Rex Graham, the owner of Graham’s Magazine, remembered Poe as a ‘polished gentleman,’ always ‘the quiet, unobtrusive, thoughtful scholar, the devoted husband, frugal in his personal expenses, punctual and unwearied in his industry, and the soul of honor in all his transactions.’ Another editor at a magazine where Poe worked remembered him as ‘a fine gentleman when he was sober. He was ever kind and courtly, and at such times every one liked him. But when he was drinking he was about one of the most disagreeable men I have met.’

“Poe’s sometimes acidic criticism could cause problems for his employers, but it also led to increased circulation. He disliked the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson and the moralistic Transcendentalists. ‘Mr. Ralph Waldo Emerson,’ Poe wrote in one issue of Graham’s, ‘belongs to a class of gentlemen with whom we have no patience whatsoever—the mystics for mysticism’s sake.’ In a review of Henry Cockton’s now-forgotten novel Stanley Thorn, Poe wrote, ‘It not only demands no reflection, but repels it, or dissipates it—much as a silver rattle the wrath of a child.’

“Poe would only last a year or two at a magazine before invariably taking up drinking again—the vocational hazard of magazine men. This would lead to profuse apologies to his young wife, Virginia, and her mother, Maria Clemm, as well as friends. After Virginia died of tuberculosis and Poe was looking to marry again for financial reasons, his lifelong friend, John Mackenzie, warned his fiancée that Poe was ‘as unstable as water. He will spend all your money and if you really do love him he will break your heart. He cannot help it. Tis his nature.'”

“Kopley regularly reexamines Poe’s stories and poems in light of his life and argues convincingly that his work contains many personal references. His story ‘The Tell-Tale Heart,’ for example, contains a scene that is evocative of Poe’s last visit to his foster father and other references to John Allan. One of his most famous stories, ‘The Cask of Amontillado,’ contains a character that is based on the writer Thomas Dunn English, with whom Poe had a very public spat in 1846. Poe was a faithful friend but a merciless enemy.”

Can AI be our friend or will it be a merciless enemy? Tevi Troy reviews Like Silicon From Clay: What Ancient Jewish Wisdom Can Teach Us About AI by Michael M. Rosen.

![]()

“Rosen takes a deep dive into AI and divides the AI commentariat into four categories. … those who think AI is transformative and are optimistic; those who think it’s transformative but are fearful; those who think it’s not transformative, but are optimistic AI is a net positive; and those who are pessimistic yet also think it’s not transformative.

“Rosen’s rubric is a good starting point, but which group is correct depends on how AI is developed. For this subject, Rosen helpfully draws from Jewish tradition to describe two models. One is the golem, the model for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein monster. The golem was a lump of clay that when infused with the right letters and rabbinical incantations became an animated creature capable of protecting the Jews from harm. As such, Rosen writes, the golem is ‘an inspiring construct for technologists to emulate: the epitome of human and even divine intellect, coupled with a purity of purpose and operation.’

“At the same time, the golem was also capable of causing significant destruction when lacking in rabbinical direction. The AI analogy is obvious. As Rosen states, it is ‘an inherently risky and potentially problematic creature that we must never allow to escape our control and that, when necessary, we must be prepared to deactivate.’

“Rosen also looks at another mystical Jewish creature, the dybbuk, which is a kind of spirit or demon that could possess people. The only way to control the dybbuk was via a maggid, a spiritual adviser who could steer the spirit in the right direction.”

“The dybbuk vision for AI is even more frightening than the golem. The possessing dybbuk can control our very actions. One potential defect that we’ve already seen along these lines in the AI world is wokeness, although any form of ideological bias is a potential danger. As Rosen describes the absurd levels to which wokeness has taken us, ‘Google appeared to allow its inner dybbuk to supplant its maggid, creating an engine that functioned as something of a parody of an ultraprogressive mentality rather than an accurate depiction of reality. … Google programmed Gemini specifically to avoid depicting white people.’ This hyper-woke programming led to the absurdity of black Nazi soldiers and black Vikings when AI was asked to depict these historically Caucasian figures.”

Weekend Beacon addendum: Congratulations to author, scholar, and Weekend Beacon contributor James Piereson on being a recipient of this year’s Bradley Prize. While Piereson is slated for a major review in a couple months, here’s an excerpt from his review of Paul Gregory’s The Oswalds: An Untold Account of Marina and Lee.

“Gregory, along with his father, introduced the Oswalds to the Russian community in Dallas, a generally professional, conservative, and anti-communist group (not Oswald’s kind of crowd). The Russian Americans responded warmly to Marina but took a disliking to Oswald, who refused to answer questions about why he defected to the Soviet Union and why he had returned to the United States. In the months that followed, they looked for opportunities to help Marina but preferred to avoid dealing with Lee.

“Marina and Lee had starkly different personalities and temperaments, so much so that Gregory wondered how they could have been married in the first place. Marina was vulnerable but curious to learn about America. Lee was insolent as well as arrogant and suspicious of anyone who did not share his Marxist politics. He kept Marina a prisoner in their run-down apartment, rebuffing efforts by others to help her and refusing to allow her to find friends or learn English. Gregory reports that Lee beat Marina on a regular basis—she had the bruises to prove it. At the same time, she ridiculed him for his sexual performance and intellectual and revolutionary pretensions. They fought regularly and separated at various times during their short stay in the Dallas area.

“On the afternoon of November 22, 1963, Gregory was watching television with friends on the campus of the University of Oklahoma when a news flash reported that President Kennedy had been shot while visiting Dallas. A short time later, he was shocked to see on screen the man who had been arrested for firing the shots at Kennedy and killing a policeman in another section of the city. Though it had been a full year since he had seen Oswald, he recognized him immediately. ‘I know that man,’ he said. That was true: He knew him as well as anyone in America at that time.”

Read the full article here