In her first week of job training, Tiffany Joseph Busch learned how to do an oil change. “If I had known it was this easy then I wouldn’t have been paying for oil changes,” she said she told her instructor.

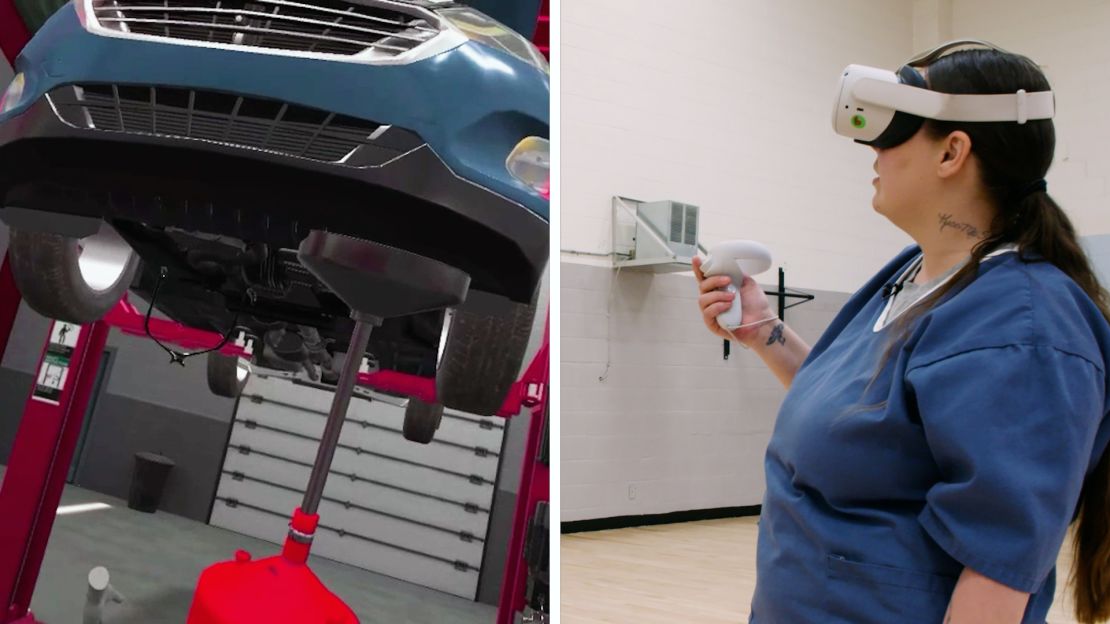

But Busch never interacted with an actual car during the training. Instead, she learned in a virtual garage, using a Meta Quest virtual reality headset.

Busch, 36, is incarcerated at the Maryland Correctional Institution for Women and is part of an early group of trainees learning skills in virtual reality that will prepare them to pursue jobs as auto technicians upon their release. For Busch, who expects to be released in June after being incarcerated on-and-off since age 19, the program will give her a crucial head start in rebuilding her life outside of prison.

“It’s dire that we get some type of training,” Busch told CNN in an interview at the prison last month. “I’m excited to be able to go home and use what we have (learned) here.”

Although virtual reality technology has been around for more than a decade, it’s still often thought of as a relatively niche technology used largely by gamers. But MCIW — in partnership with Baltimore-based nonprofit Vehicles for Change, which developed the program — is exploring whether VR headsets could make career training opportunities more accessible inside prisons. The ultimate goal is to reduce recidivism rates by ensuring incarcerated people have a clear path to good-paying jobs once they’re released.

Across the United States, auto technicians are in strong demand; trade groups say the industry sees tens of thousands of jobs go unfilled each year. And in Maryland, such positions often pay above the state’s $15 per hour minimum wage.

“This isn’t rocket science. It’s a matter of getting people a job that leads to a career, and we can keep people out of prison,” said Vehicles for Change President Martin Schwartz. “If they can get a job that’s going to pay $16 to $20 an hour, we can change the trajectory of that recidivism rate.”

A job paying $16-$20 an hour could ‘change the trajectory’ for inmates. Here’s how VR could make that possible

Vehicles for Change was founded in 1999 to provide low-income families with affordable cars. In 2016, the nonprofit developed an in-person auto technician training program for formerly incarcerated people, where participants would receive paid job training while repairing cars to go to the organization’s clients.

The organization has relationships with employers such as Napa Auto Parts and AAA, representatives of which sit on its board, to help graduates secure full-time work after completing the program.

But during the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of trainees that Vehicles for Change could safely allow into its garages dipped, so Schwartz began exploring alternate ways of delivering the training.

He was eventually connected to software company HTX Labs, which had built virtual reality training programs for the US Air Force and later designed the auto mechanic training program for Vehicles for Change.

In addition to MCIW, the nonprofit is also piloting the VR auto technician training program in correctional facilities in Texas and Virginia.

For leaders in Maryland’s correctional department, the VR program provided a way to expand job training for a field in need of workers to the Women’s Correctional Institute quickly and easily. The corrections department works “very closely with (the state’s) Department of Labor to determine what the industry needs are, where the vacancies are,” according to Carolyn Scruggs, Maryland’s secretary of public safety and correctional services.

Several of the state’s other prisons have hands-on mechanic training programs, but building a new garage means having to find the space and bringing in expensive equipment — processes further complicated by the strict security measures prisons must maintain. Although the headsets cost nearly $500 each, they’re still more affordable than providing conventional, hands-on training programs.

“Bringing in VR, it eliminates all that needed space or funding that we would need to build an entire classroom,” said Danielle Cox, director of education at the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services, who oversees the correctional department’s 26 different job training programs.

“Also, it gets them something within a couple of weeks that would take a longer time if they were doing hands-on within the classroom,” Cox said. “So we can have some women … take this opportunity and actually get out and get a job as soon as they are released.”

Now on its third cohort, the program at MCIW has graduated 15 women since it began last year.

The women at MCIW come to the facility’s gymnasium, reminiscent of a high school gym, for the training. When they put the headsets on, they’re transported to a virtual auto repair garage, where they can operate the car lift and use various tools.

By the time they complete the program, trainees are prepared for jobs as tire lube technicians — roles available at places like Jiffy Lube or Mr. Tire — and for the Automotive Service Excellence exam, the nationally recognized certification for auto mechanics.

“I think the best part about it, for incarcerated people, is you get to escape from this place, and it reminds you that there is something outside of here,” said Meagan Carpenter, another one of the MCIW trainees.

“I want to be able to show my children, especially my daughter, that anything a man can do, we can do better or the same,” she said. “And I want to be a good representative for this program … sometimes we just need that one program to have faith in us and give us an opportunity.”

But is it really possible to learn how to fix a car in virtual reality without ever interacting with a real vehicle? Carpenter said she feels “100% confident in my abilities.”

And Schwartz said he’s certain about the potential for VR training, too. He added that given the need for auto workers, employers are often happy to show trainees how to take what they’ve learned in the digital world to operate safely in a real garage.

“Virtual reality is number one going to be the way we train the skill trades in five years across the board,” he said. “This technology is going to change, certainly (in-prison) training, but it’s going to make a huge difference for the marginalized populations that we have in this country that can’t afford to go to a community college to get an automotive degree or a trade school … We’re not only going to fill the gap for trades, but we’re going to change poverty in this country by using virtual reality.”

Read the full article here